Scientists with the new Children’s Research Institute at UT Southwestern Medical Center have identified the environment in which blood-forming stem cells survive and thrive within the body, an important step toward increasing the safety and effectiveness of bone-marrow transplantation.

Scientists with the new Children’s Research Institute at UT Southwestern Medical Center have identified the environment in which blood-forming stem cells survive and thrive within the body, an important step toward increasing the safety and effectiveness of bone-marrow transplantation.

Institute investigators led by Dr. Sean Morrison asked which cells are responsible for the microenvironment that nurtures haematopoietic stem cells, which produce billions of new blood cells every day. The answer: endothelial and perivascular cells, which line blood vessels.

“Although scientists have searched for decades to identify the stem cell home, this is the first study to reveal the cells that are functionally responsible for the maintenance of blood-forming stem cells in the body,” said Dr. Morrison, director of the new institute and senior author of the study available Jan. 26 in Nature. “This discovery will lead to the identification of the mechanisms by which cells promote stem cell maintenance and expansion.”

Scientists already have determined how to make large quantities of stem cells and how to change these cells into those of the nervous system, skin and other tissues. But they have been stymied by similar efforts to make blood-forming stem cells. A key obstacle has been the lack of understanding about the microenvironment, or niche, in which blood-forming stem cells reside in the body.

In the first breakthrough from the Children’s Research Institute, Dr. Morrison’s laboratory addressed this issue by systematically determining which cells are the sources of stem cell factor, a protein required for the maintenance of blood-forming stem cells. His team swapped out the mouse gene responsible for stem cell factor with a gene from jellyfish that encodes green fluorescent protein. The cells that glowed green were endothelial and perivascular cells, revealing them as the creators of the niche that nurtures healthy blood-forming stem cells.

Additional lab work showed that blood-forming stem cells become depleted if stem cell factor is eliminated from either endothelial or perivascular cells. Loss of stem cell factor from both of these sources caused stem cells to virtually disappear.

The research has implications for bone marrow and umbilical cord blood transplants, Dr. Morrison said. If scientists can identify the remaining signals by which perivascular cells promote the expansion of blood-forming stem cells, then they may be able to replicate these signals in the laboratory. Doing so will make it possible to expand blood-forming stem cells prior to transplantation into patients, thereby increasing the safety and effectiveness of this widely used clinical procedure.

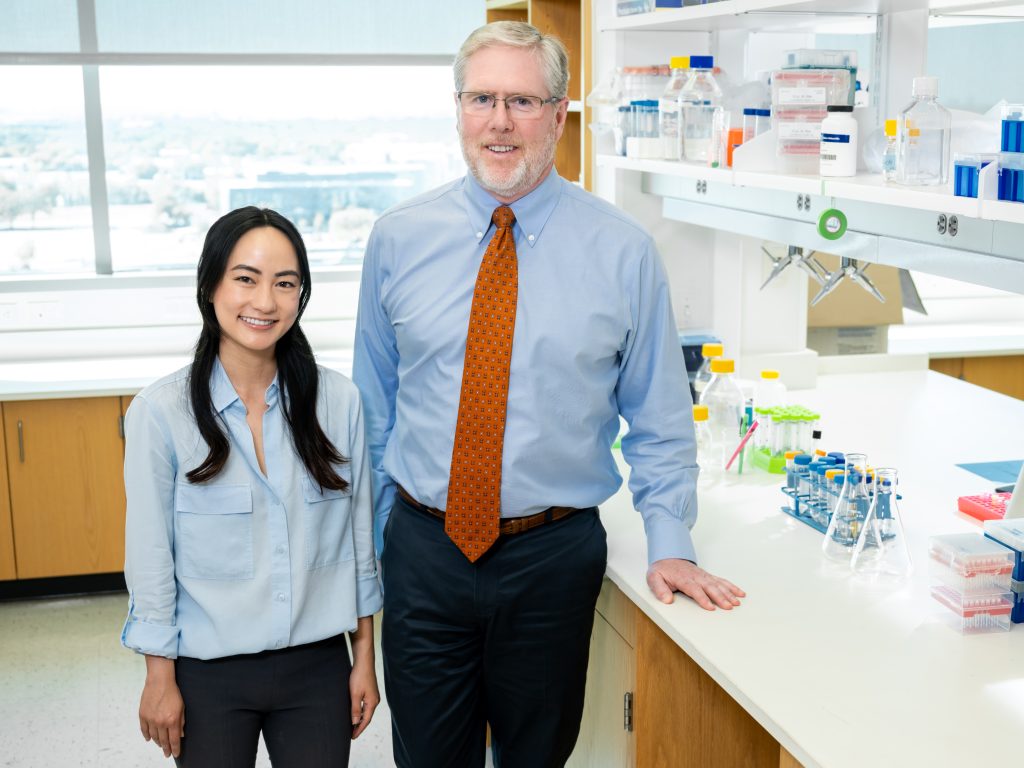

Dr. Morrison’s paper is the first to emerge from the Children’s Research Institute at UT Southwestern, a pioneering venture that combines the medical center’s research prowess with the world-class clinical expertise of Children’s Medical Center Dallas. Under Dr. Morrison’s leadership, the institute is focusing on research at the interface of stem cell biology, cancer, and metabolism that has the potential to reveal new strategies for treating disease.

The institute currently has more than 30 scientists and will eventually include 150 scientists in 15 laboratories led by UT Southwestern faculty members. Dr. Morrison’s lab focuses on adult stem cell biology and cancers of the blood, nervous system and skin.

The Nature paper’s first author is Dr. Lei Ding, postdoctoral research fellow at the Children’s Research Institute and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Scientists from the University of Michigan and Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory also contributed to the study, which was supported by the HHMI and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

About the Children’s Research Institute

Children’s Medical Center Research Institute at UT Southwestern (CRI) is a joint venture positioned to build upon the comprehensive clinical expertise of Children’s Medical Center of Dallas and the internationally recognized scientific environment of UT Southwestern Medical Center. CRI’s mission is to perform transformative biomedical research to better understand the biological basis of disease. Established in 2011, CRI is creating interdisciplinary groups of exceptional scientists and physicians to pursue research at the interface of regenerative medicine, cancer biology and metabolism, which together hold unusual potential for discoveries that can yield groundbreaking advances in science and medicine.