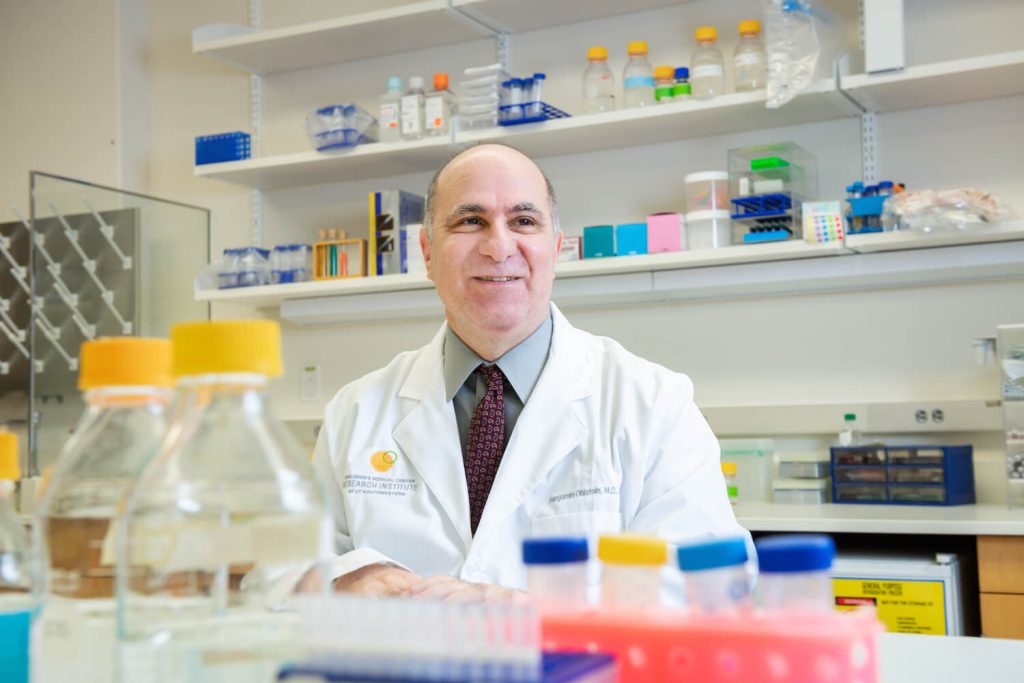

Children’s Medical Center Research Institute at UT Southwestern (CRI) recently recruited Dr. Ben Ohlstein to become the institute’s ninth faculty member and principal investigator. He earned his M.D. and Ph.D. degrees from UT Southwestern Medical Center in 2002 and completed a postdoctoral fellowship at the Carnegie Institution for Science in Baltimore, Maryland, in Allan C. Spradling’s laboratory in 2007. After his postdoctoral studies, Dr. Ohlstein joined Columbia University Medical Center where he was an associate professor of genetics and development and a member of the Columbia Stem Cell Initiative. Recently, Dr. Ohlstein shared his thoughts on joining CRI and the goals he hopes to achieve through his research.

What are you researching?

In nearly all tissues, adult stem cells play a critical role in maintaining and repairing damaged tissues and organs over the course of our lives. The intestine, which is responsible for regulating nutrition levels, satiety, and moving food through the digestive tract, is no different. Cells in our intestines have high cell turnover rates and need to link the production of new cells with the loss of old cells to keep tissues healthy and functioning. When these mechanisms become corrupted or break down, serious consequences can occur, including compromised tissue function, overgrowth of cells, and cancer.

In my lab, we use the intestinal tract of the fruit fly, also known as Drosophila, as a model to study the normal development of intestinal stem cells and how abnormalities in this process can lead to diseases like cancer, diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, and even premature aging. We employ a combination of genetic and biochemical approaches to precisely determine how cells of the intestine grow and expand during the course of normal development and how mutations or changes in this process can result in disease. Ultimately, a better understanding of the biology of the Drosophila intestine will help with the diagnosis, treatment, and cures of various conditions that affect the human gastrointestinal tract.

Why did you decide to join the CRI?

In the past decade, it has been increasingly clear that the mechanisms uncovered in the fly gut by my lab and others are similar to those discovered by researchers studying the human intestine. The next logical step is to replicate our work in humans, but making this shift comes with a number of obstacles. I knew if I wanted to incorporate studies on the human gut into the lab’s research focus, I needed to find a world-class institute like CRI to make the transition. The scientific environment here is robust, and each member is a leader in their field. The resources available in CRI are also cutting edge and readily available. I’m counting on the highly interactive nature of CRI to help to foster collaborations between my lab and the labs of others at the institute with expertise in human stem cell biology to facilitate our plans to translate our basic research programs into clinical treatments for patients.

How do you expect your work will one day help patients?

In adults, diarrhea is often seen as a mere nuisance. However, in infants and children, diarrhea is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Prolonged diarrhea can severely affect normal childhood development. Drastic approaches such as intravenous nutrition and bowel transplants are often necessary to treat patients but are fraught with their set of problems. Both infectious and genetic causes of diarrhea have been identified, but how these result in disease is poorly understood. Most of the genes implicated in diarrheal diseases are also present in the fruit fly, suggesting that the fly could be used as a model to study diarrheal diseases. We plan to create flies that lack these genes and study the effect on the gastrointestinal tract. This approach will allow us to gain insight into disease mechanisms and rapidly identify new and better treatments for patients.

What led to your career in science?

My career in science began quite fortuitously. A year or so after graduating from college, I decided to return to school at The University of Texas at Austin to pursue coursework in molecular biology to fulfill part of the requirements for a career as a patent attorney. To help finance my studies, I found a work-study position as a dishwasher in the lab of Dr. Dean Appling. During my time there, I was given my own research project with minimal supervision by a postdoctoral fellow and, for the first, time became exposed to the joys of carrying out independent scientific research.

Later on, when I was walking down the halls of the chemistry building, I noticed an ad for a summer undergraduate research fellowship at UT Southwestern. I decided to apply and was fortunate to be accepted into the program under the supervision of Dr. Helen Yin. Given a second opportunity to actively participate in an independent research project, I realized that a job as scientific researcher could fulfill my desire for a rewarding and creative career. About a year later, I matriculated into the Medical Scientist Training Program at UT Southwestern where I earned my M.D. and my Ph.D. Ever since then, I have been actively involved in basic science research.

How do you spend your time outside the lab?

I love to cook. Cooking and scientific research actually have a lot in common. Both require great ingredients, flawless technique, trial and error, and good taste. And in the end, if everything is done correctly, the results are delicious.