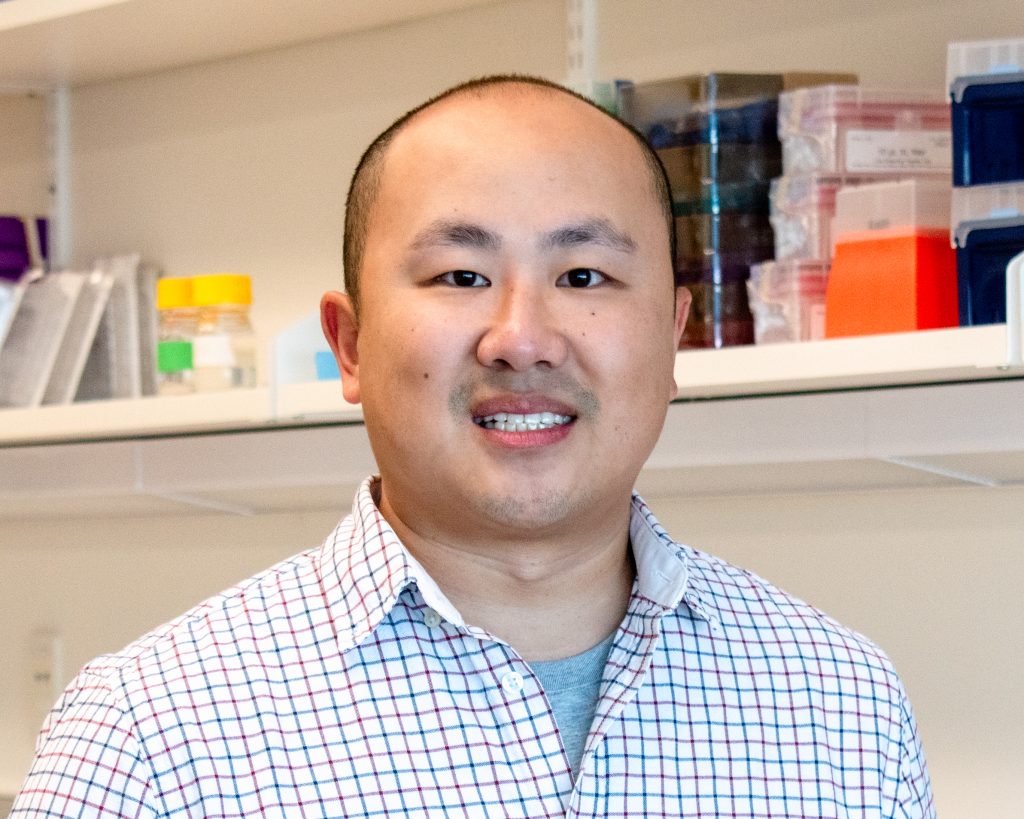

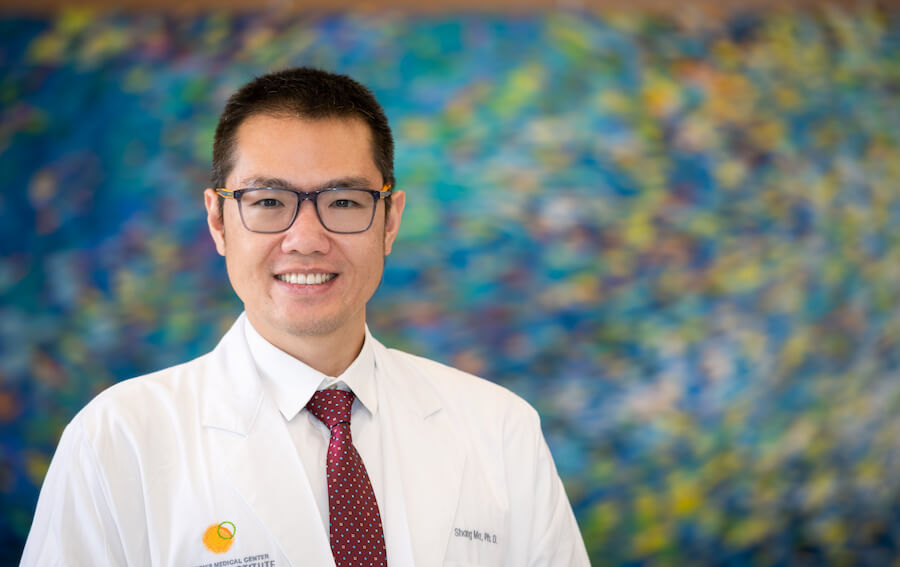

Shang Ma, Ph.D., recently joined the institute as CRI’s newest faculty member and principal investigator. He earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of British Columbia and his Ph.D. in cellular and molecular biology from the University of Wisconsin in Madison. There, he focused on chemical signaling pathways that mediated mammalian brain development. In 2015, Dr. Ma joined Dr. Ardem Patapoutian’s group at Scripps Research to study how cells sense mechanical forces during pathogenesis. During this postdoc training, he discovered that overactive PIEZO mechanosensitive ion channels play important roles in various human disorders.

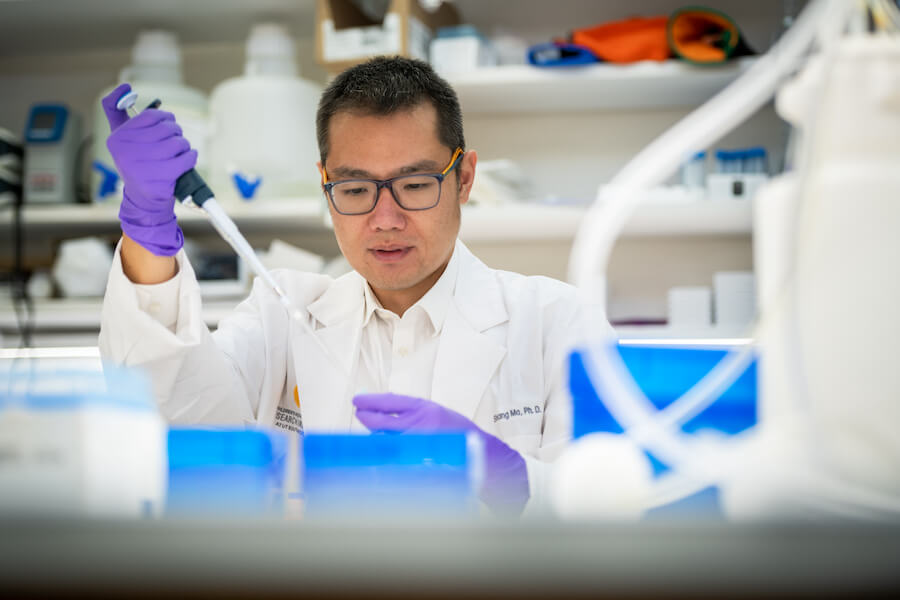

In CRI, the Ma lab uses an interdisciplinary approach to understand how cells sense and process mechanical stimuli in health and disease. Dr. Ma recently sat down and shared his thoughts on joining CRI and the goals he hopes to achieve through his research.

Why did you decide to join CRI?

CRI’s core mission is what initially attracted me. This is an institute with a deep focus on the fundamental questions related to the molecular basis of human diseases. I knew I wanted to establish my research group in a place where the philosophy and intellectual environment would support the translation of basic science research from the lab into something that could help patients. CRI is especially equipped to achieve this mission with its state-of-the-art core facilities that accelerate research and its efficient support teams that allow scientists to focus on their research instead of being disrupted by administrative affairs.

What are you researching?

I am interested in understanding how physical forces affect cellular processes. Traditionally, biomedical research has been dominated by the study of chemical signals, for example, how hormones regulate metabolism and how neurotransmitters impact brain functions. Yet nearly all cells experience mechanical stimuli as well—cells are pushed, pressured, and sheared constantly. Many diseases, including deafness, osteoporosis, and hypertension, are caused by a cell’s inability to sense mechanical stimuli properly. Our understanding of such “mechanosensing” pathways remains very limited. I hope that an in-depth study of mechanotransduction pathways will allow us to find new, promising drug targets for different diseases.

How do you expect your work will one day help patients?

In many situations, issues related to mechanotransduction can go wrong, leading to disease. In healthy patients, red blood cells have the ability to reduce their volumes in response to physical forces exerted on them. This is what allows them to squeeze into narrow capillaries that are part of the circulatory system. In some instances, the mechanosensing pathways that regulate this change become oversensitive, leading to misshaped red blood cells and resulting in anemia-related problems.

Many traditional avenues of care are focused on treating symptoms, but if we can identify the incorrectly activated mechanosensing activity and find drugs to inhibit it, we will have new ways to cure these blood-related health problems.

What would you be if you were not a scientist?

I think I would want to be a detective. I used to like reading Sherlock Holmes to see how he used logic and intuition to solve problems. Being a detective is actually a career I am still interested in! The reason is that I love secrets. Scientists look for secrets in natural things, while detectives look for secrets in people’s activities. There is some great crossover between the two.

What do you like to do when you’re not in the lab?

I’m an indoor person. Museums, art galleries, concerts, temples, and bookstores are my favorites. In Dallas, I especially love the Dallas Museum of Art, the Nasher Sculpture Center, and the Dallas Symphony. I also enjoy watching sports games with friends and colleagues. Watching the World Cup is a must, although, luckily, this can be done in the lab! I love walking my dog in different places as well.