Scientists at the Children’s Medical Center Research Institute at UT Southwestern (CRI) report that inactivating a certain protein-coding gene promotes liver tissue regeneration in mammals.

Scientists at the Children’s Medical Center Research Institute at UT Southwestern (CRI) report that inactivating a certain protein-coding gene promotes liver tissue regeneration in mammals.

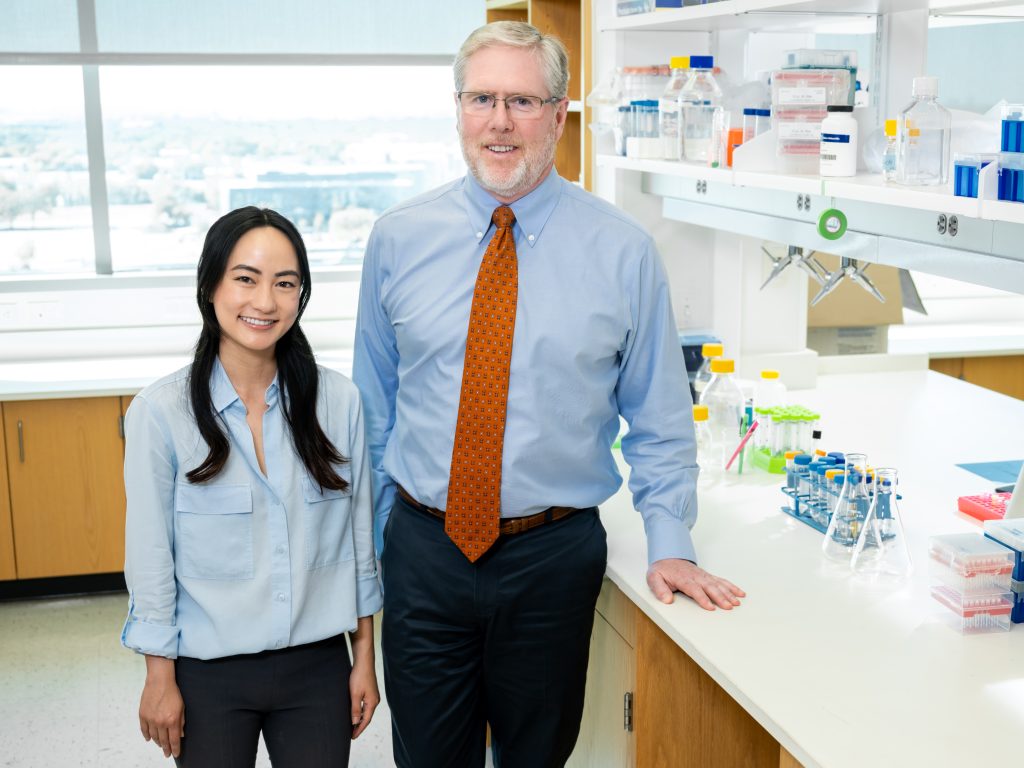

“This research gives us ideas about new ways to treat liver damage or chronic liver disease,” said senior author Dr. Hao Zhu, an Assistant Professor at CRI with joint appointments in Internal Medicine and Pediatrics at UT Southwestern Medical Center. The study was published this week in the journal Cell Stem Cell.

Tails in lizards and arms in starfish show an astounding ability to regrow, but mammals have partially lost the capacity to extensively regenerate body parts, Dr. Zhu said. The liver is unique among human solid organs in its robust regenerative capability. A healthy liver can regenerate up to 70 percent of its tissue after injury, he explained.

However, when the liver has been repeatedly damaged – by chemical toxins or chronic disease – it loses its ability to regenerate. Following repeated injuries, cirrhosis or scar tissue forms, greatly increasing the risk of cancer, said Dr. Zhu, who also treats liver cancer patients at Parkland Memorial Hospital. The Zhu laboratory studies both regeneration, when cells proliferate to repair an organ, and cancer, when cells proliferate out of control.

The National Cancer Institute (NCI) reports that liver cancer deaths increased at the highest rate of all common cancers from 2003-2012. In addition to cirrhosis, risk factors for liver cancer include infections caused by the hepatitis C virus (HCV), liver damage from alcohol or other toxins, chronic liver disease, and certain rare genetic disorders.

The National Cancer Institute (NCI) reports that liver cancer deaths increased at the highest rate of all common cancers from 2003-2012. In addition to cirrhosis, risk factors for liver cancer include infections caused by the hepatitis C virus (HCV), liver damage from alcohol or other toxins, chronic liver disease, and certain rare genetic disorders.

Dr. Zhu began his investigation by studying a mouse that lacked Arid1a, the mouse version of a gene associated with some human cancers.

“In humans, the gene ARID1A is mutated in several cancers, including liver cancer, pancreatic cancer, breast cancer, endometrial cancer, lung cancer, the list goes on,” Dr. Zhu said. “It is not mutated in every type of cancer, but in a significant number. Those mutations are found in 10 to 20 percent of all cancers, and the mutations render the gene inactive.”

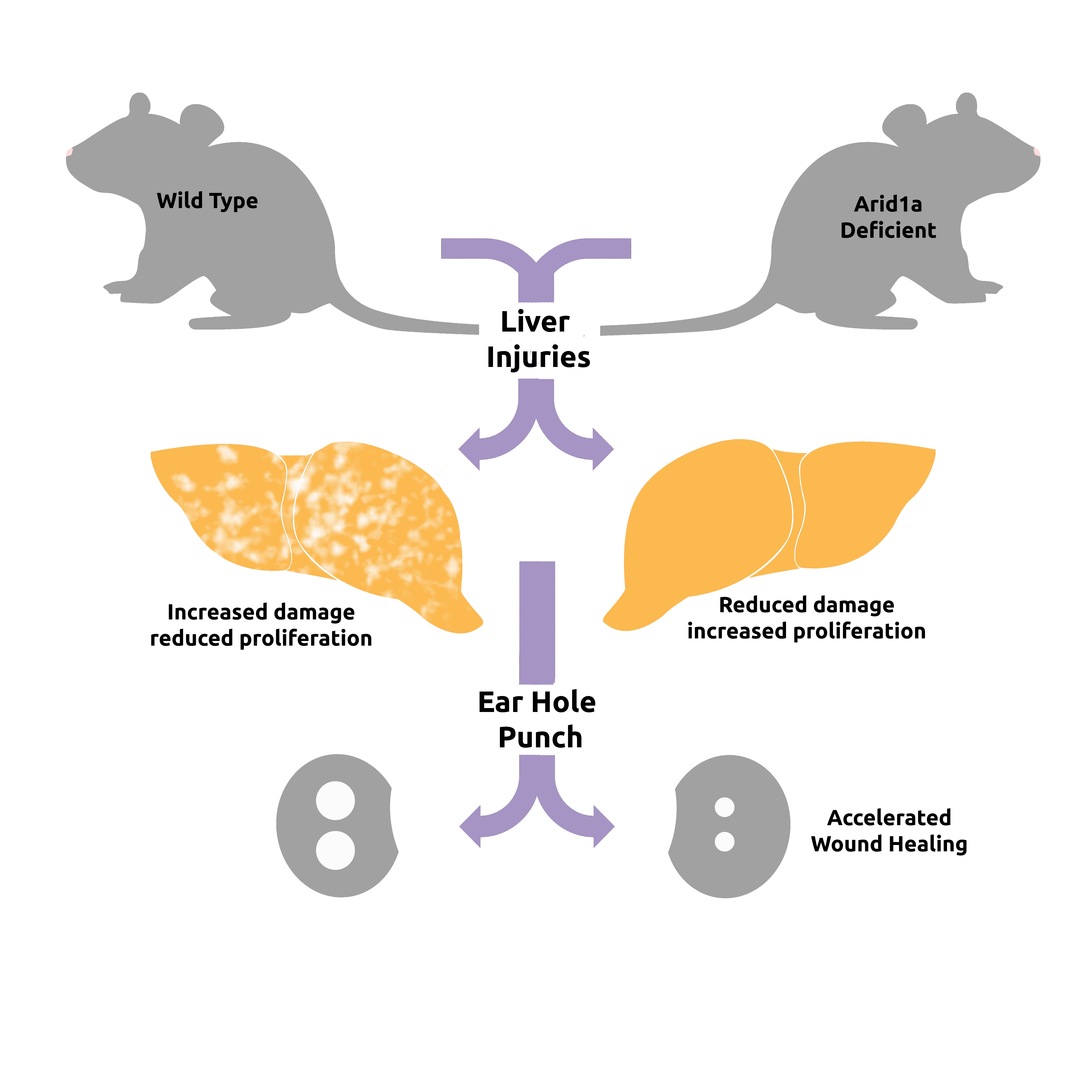

Based on this association, the researchers hypothesized that mice lacking Arid1a would develop liver damage and, eventually, liver cancer. They were surprised when the opposite proved to be the case – no liver damage occurred. In fact, livers of the mice regenerated faster and appeared to function better, he added.

“The livers were resistant to tissue damage and healed better, which are two good things – like playing offense and defense at the same time,” he said. “These results opened up a whole new avenue of investigation for us, and through that investigation we found a new function for this gene.”

On observation, livers in the mice without the gene appeared healthier. Blood tests confirmed improved liver function. When researchers deleted the gene in mice with various liver injuries, they found that the livers replaced tissue mass quicker and showed reduced fibrosis in response to chemical injury. Also, other tissues such as wounded skin healed faster in Arid1a-deficient mice.

No drugs are currently available to mimic a lack of this protein, although the researchers are using a grant from the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) to search for one.

“We want to identify small molecules that mimic the effect of these genetic findings. The ideal drug would be one that helps the liver heal while inhibiting the development of cancer. That would be the perfect drug for my patients,” said Dr. Zhu, a CPRIT Scholar in Cancer Research.

Dr. Zhu said loss of the gene and the protein it expresses may accelerate regeneration by reorganizing how genes are packaged in the genome so that the cells can more easily switch back and forth toward a more regenerative state, sort of like a toggle switch.

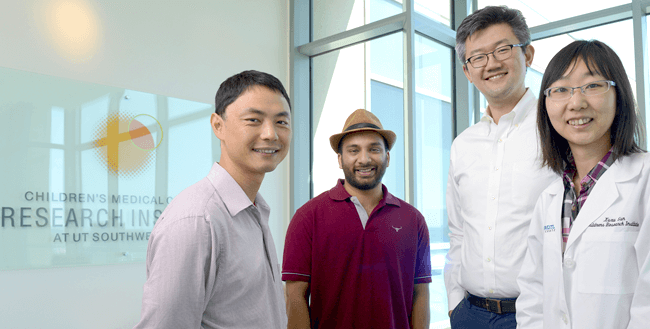

“Somehow, loss of this gene seems to make it easier for the cell to go back and forth,” he said. “This study opens up new areas to investigate how to rejuvenate tissues without necessarily increasing cancer risk, although many more tests will have to be done to determine how the risk of all types of liver cancers are altered.” Co-authors included lead author Dr. Xuxu Sun and Dr. Xin Liu, postdoctoral researchers at CRI; Dr. Jen-Chieh Chuang, Assistant Instructor at CRI; Mahsa Sorouri, research assistant at CRI; Lin Li, senior research scientist at CRI; Dr. Jian Xu, Assistant Professor at CRI and Pediatrics at UTSW; graduate students Cemre Celen, Shuyuan Zhang, and Yi-Chun Kuo; Liem Nguyen, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute International Student Research fellow; Dr. Sam Wang, Assistant Professor of Surgery at UTSW; Dr. Ibrahim Nassour, surgical resident at UTSW; Thomas Maples, medical student at UTSW; Mohammed Kanchwala, a computational biologist in UTSW’s Eugene McDermott Center for Human Growth and Development, and Dr. Chao Xing, Associate Professor in the McDermott Center and of Clinical Sciences.

Other contributors were from First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University, UT Southwestern’s sister institution in Guangzhou, China; the University of California, San Diego; Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai; and the University of Michigan. This study was supported by the American Heart Association, the March of Dimes Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the Burroughs Welcome Fund, CPRIT, and donors to the Children’s Medical Center Foundation.

About CRI

Children’s Medical Center Research Institute at UT Southwestern (CRI) is a joint venture established in 2011 to build upon the internationally recognized scientific excellence of UT Southwestern Medical Center and the comprehensive clinical expertise of Children’s Medical Center, the flagship hospital of Children’s HealthSM. CRI’s mission is to perform transformative biomedical research to better understand the biological basis of disease, seeking breakthroughs that can change scientific fields and yield new strategies for treating disease. Located in Dallas, Texas, CRI is creating interdisciplinary groups of exceptional scientists and physicians to pursue research at the interface of regenerative medicine, cancer biology and metabolism, fields that hold uncommon potential for advancing science and medicine. More information about CRI is available on its website: cri.utsw.edu..